The paper has been accepted by Icaurs, and is also available via

WWW download as

UNCOMPRESSED POSTSCRIPT (3.8 Mb), at

http://www.obs-nice.fr/gladman/Extended.ps

G-ZIPPED POSTSCRIPT (0.52 Mb), at

http://www.obs-nice.fr/gladman/Extgz.ps.gz

ORBIT OF SCATTERED DISK OBJECTS AND 2000 CR105

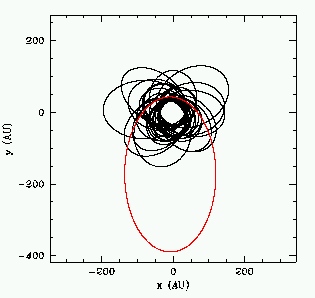

This figure compares the orbits of the other scattered disk objects

with that we have estimated for 2000 CR105.

This figure shows the orbits of all the known scattered disk objects (SDOs)

as well as the much larger orbit of 2000 CR105 (in red).

The SDOs are objects which are on large looping orbits; the most developed

theories for the creation of the scattered disk produce these orbits by

gravitational scattering due to Neptune, which hurls them out to external

orbits which take hundreds of year to circulate around the Sun.

Numerical calculations have shown that some of the objects can rest in

this state for the 4.5-billion year lifetime of the Solar System.

The first recognized SDO was 1996 TL66, discovered by Luu et al. in 1996

(reprint in pdf format available on the www).

About two dozen such SDOs are now known, many of them have been discovered

and tracked by

C. Trujillo et al.

The figure shows that 2000 CR105 journeys far from the Sun, several times

further than the other SDOs.

There are long-period comets that journey much farther away towards the

Oort cloud.

The interesting facet of CR105's orbit is NOT its large size, but rather

the fact that its perihelion (distance of closest approach to the Sun) is

larger than any other known Solar System object.

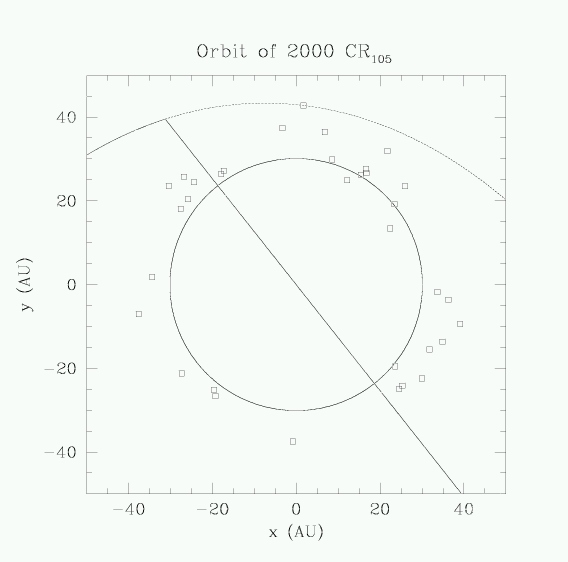

This figure shows a dot at the perihelion position of each of the SDOs

plotted in the previous diagram, marking the point of closest solar approach.

Only the orbit of 2000 CR105 is shown, and is dotted when the orbit is below

the plane of the other planets and solid when above (2000 CR105's orbit is

inclined about 20 degrees with respect to the plane of the solar system).

The circle shows the orbit of Neptune, for reference. The straight solid

line is the `line of nodes' of CR105, showing where its orbit intersects

the plane of the planets.

CR105 is currently past it's line of nodes and heading out farther into

deep space to the top left of this plot.

It is striking that this roughly 400-km object would be visible, even

to the most powerful telescopes, for only a tiny fraction of its orbital

period, while it is in the tiny portion near pericenter of its more than

3000-year orbital journey.

Because the perihelia of the SDOs are near Neptune, it is thought

that they are likely to be objects that in the ancient past had a close

pass to Neptune and the planet's gravity `sling-shotted' them out onto large

orbits. Dynamical computer simulations by

Hal Levison

and

Martin Duncan

show in detail how the orbits of this population are distributed.

However, these simulations do NOT produce orbits with PERIHELIA as far

away as 2000 CR105 (although orbits as LARGE do occur).

Simply put,

this is because the objects that are scattered out from Neptune by close

encounters are `close' to the planet at the instant of scattering.

The object will then return to that point after one orbit and only continual

long-term `wandering' of the perihelion due to encounters that are not

as close can allow the perihelion to drift away from Neptune.

The numerical simulations seem to show that it is possible for perihelia to

eventually reach distances as far away as 40 AU. However, CR105's perihelion

if 4.3 AU farther out than that (almost the distance from the Sun to Jupiter!)

Therefore, the simulations do not seem to produce objects like this, and we

believe that for the moment 2000 CR105 should NOT be classed as an SDO.

In the preprint (available above) we discuss various scenarios which could

have produced this fascinating object.

Page maintained by: Brett Gladman Observatoire de la Cote d'AzurURL: http://www.obs-nice.fr/gladman